Visual search is one of the most complex and fiercely competed sectors of our industry. Earlier this month, Bing announced their new visual search mode, hot on the heels of similar developments from Pinterest and Google.

Ours is a culture mediated by images, so it stands to reason that visual search has assumed such importance for the world’s largest technology companies. The pace of progress is certainly quickening; but there is no clear visual search ‘winner’ and nor will there be one soon.

The search industry has developed significantly over the past decade, through advances in personalization, natural language processing, and multimedia results. And yet, one could argue that the power of the image remains untapped.

This is not due to a lack of attention or investment. Quite the contrary, in fact. Cracking visual search will require a combination of technological nous, psychological insight, and neuroscientific know-how. This makes it a fascinating area of development, but also one that will not be mastered easily.

Therefore, in this article, we will begin with an outline of the visual search industry and the challenges it poses, before analyzing the recent progress made by Google, Microsoft and Pinterest.

What is visual search?

We all partake in visual search every day. Every time we need to locate our keys among a range of other items, for example, our brains are engaged in a visual search.

We learn to recognize certain targets and we can locate them within a busy landscape with increasing ease over time.

This is a trickier task for a computer, however.

Image search, in which a search engine takes a text-based query and tries to find the best visual match, is subtly distinct from modern visual search. Visual search can take an image as its ‘query’, rather than text. In order to perform an accurate visual search, search engines require much more sophisticated processes than they do for traditional image search.

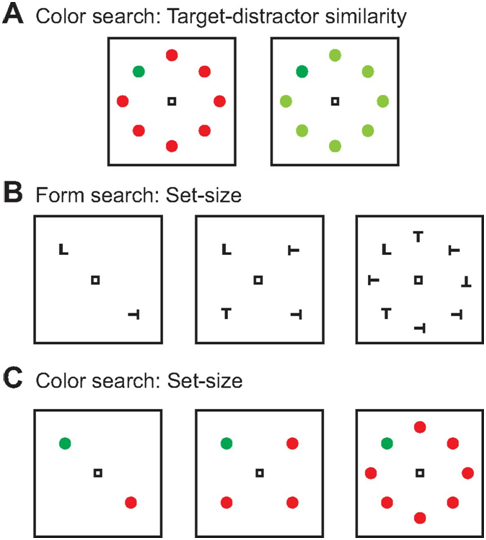

Typically, as part of this process, deep neural networks are put through their paces in tests like the one below, with the hope that they will mimic the functioning of the human brain in identifying targets:

The decisions (or inherent ‘biases’, as they are known) that allow us to make sense of these patterns are more difficult to integrate into a machine. When processing an image, should a machine prioritize shape, color, or size? How does a person do this? Do we even know for sure, or do we only know the output?

As such, search engines still struggle to process images in the way we expect them to. We simply don’t understand our own biases well enough to be able to reproduce them in another system.

There has been a lot of progress in this field, nonetheless. Google image search has improved drastically in response to text queries and other options, like Tineye, also allow us to use reverse image search. This is a useful feature, but its limits are self-evident.

For years, Facebook has been able to identify individuals in photos, in the same way a person would immediately recognize a friend’s face. This example is a closer approximation of the holy grail for visual search; however, it still falls short. In this instance, Facebook has set up its networks to search for faces, giving them a clear target.

At its zenith, online visual search allows us to use an image as an input and receive another, related image as an output. This would mean that we could take a picture with a smartphone of a chair, for example, and have the technology return pictures of suitable rugs to accompany the style of the chair.

The typically ‘human’ process in the middle, where we would decipher the component parts of an image and decide what it is about, then conceptualize and categorize related items, is undertaken by deep neural networks. These networks are ‘unsupervised’, meaning that there is no human intervention as they alter their functioning based on feedback signals and work to deliver the desired output.

The result can be mesmerising, as in the below interpretations of an image of Georges Seurat’s ‘A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte’ by Google’s neural networks:

This is just one approach to answering a delicate question, however.

There are no right or wrong answers in this field as it stands; simply more or less effective ones in a given context.

We should therefore assess the progress of a few technology giants to observe the significant strides they have made thus far, but also the obstacles left to overcome before visual search is truly mastered.

Bing visual search

In early June at TechCrunch 50, Microsoft announced that it would now allow users to “search by picture.”

This is notable for a number of reasons. First of all, although Bing image search has been present for quite some time, Microsoft actually removed its original visual search product in 2012. People simply weren’t using it since its 2009 launch, as it wasn’t accurate enough.

Furthermore, it would be fair to say that Microsoft is running a little behind in this race. Rival search engines and social media platforms have provided visual search functions for some time now.

As a result, it seems reasonable to surmise that Microsoft must have something compelling if they have chosen to re-enter the fray with such a public announcement. While it is not quite revolutionary, the new Bing visual search is still a useful tool that builds significantly on their image search product.

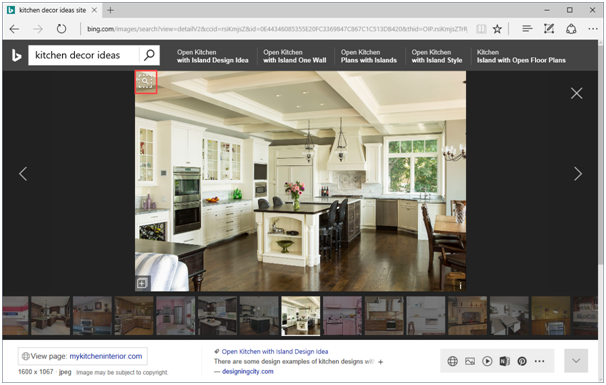

A Bing search for “kitchen decor ideas” which showcases Bing’s new visual search capabilities

What sets Bing visual search apart is the ability to search within images and then expand this out to related objects that might complement the user’s selection.

A user can select specific objects, hone in on them, and purchase similar items if they desire. The opportunities for retailers are both obvious and plentiful.

It’s worth mentioning that Pinterest’s visual search has been able to do this for some time. But the important difference between Pinterest’s capability and Bing’s in this regard is that Pinterest can only redirect users to Pins that businesses have made available on Pinterest – and not all of them might be shoppable. Bing, on the other hand, can index a retailer’s website and use visual search to direct the user to it, with no extra effort required on the part of either party.

Powered by Silverlight technology, this should lead to a much more refined approach to searching through images. Microsoft provided the following visualisation of how their query processing system works for this product:

Microsoft combines this system with the structured data it owns to provide a much richer, more informative search experience. Although restricted to a few search categories, such as homeware, travel, and sports, we should expect to see this rolled out to more areas through this year.

The next step will be to automate parts of this process, so that the user no longer needs to draw a box to select objects. It is still some distance from delivering on the promise of perfect, visual search, but these updates should at least see Microsoft eke out a few more sellable searches via Bing.

Google Lens

Google recently announced its Lens product at the 2017 I/O conference in May. The aim of Lens is really to turn your smartphone into a visual search engine.

Take a picture of anything out there and Google will tell you what the object is about, along with any related entities. Point your smartphone at a restaurant, for example, and Google will tell you its name, whether your friends have visited it before, and highlight reviews for the restaurant too.

With Google Lens, your smartphone camera won’t just see what you see, but will also understand what you see to help you take action. #io17 pic.twitter.com/viOmWFjqk1

— Google (@Google) May 17, 2017

This is supplemented by Google’s envious inventory of data, both from its own knowledge graph and the consumer data it holds.

All of this data can fuel and refine Google’s deep neural networks, which are central to the effective functioning of its Lens product.

Google-owned company DeepMind is at the forefront of visual search innovation. As such, DeepMind is also particularly familiar with just how challenging this technology is to master.

The challenge is no longer necessarily in just creating neural networks that can understand an image as effectively as a human. The bigger challenge (known as the ‘black box problem’ in this field) is that the processes involved in arriving at conclusions are so complex, obscured, and multi-faceted that even Google’s engineers struggle to keep track.

This points to a rather poignant paradox at the heart of visual search and, more broadly, the use of deep neural networks. The aim is to mimic the functioning of the human brain; however, we still don’t really understand how the human brain works.

As a result, DeepMind have started to explore new methods. In a fascinating blog post they summarized the findings from a recent paper, within which they applied the inductive reasoning evident in human perception of images.

Drawing on the rich history of cognitive psychology (rich, at least, in comparison with the nascent field of neural networks), scientists were able to apply within their technology the same biases we apply as people when we classify items.

DeepMind use the following prompt to illuminate their thinking:

“A field linguist has gone to visit a culture whose language is entirely different from our own. The linguist is trying to learn some words from a helpful native speaker, when a rabbit scurries by. The native speaker declares “gavagai”, and the linguist is left to infer the meaning of this new word. The linguist is faced with an abundance of possible inferences, including that “gavagai” refers to rabbits, animals, white things, that specific rabbit, or “undetached parts of rabbits”. There is an infinity of possible inferences to be made. How are people able to choose the correct one?”

Experiments in cognitive psychology have shown that we have a ‘shape bias’; that is to say, we give prominence to the fact that this is a rabbit, rather than focusing on its color or its broader classification as an animal. We are aware of all of these factors, but we choose shape as the most important criterion.

“Gavagai” Credit: Misha Shiyanov/Shutterstock

DeepMind is one of the most essential components of Google’s development into an ‘AI-first’ company, so we can expect findings like the above to be incorporated into visual search in the near future. When they do, we shouldn’t rule out the launch of Google Glass 2.0 or something similar.

Pinterest Lens

Pinterest aims to establish itself as the go-to search engine when you don’t have the words to describe what you are looking for.

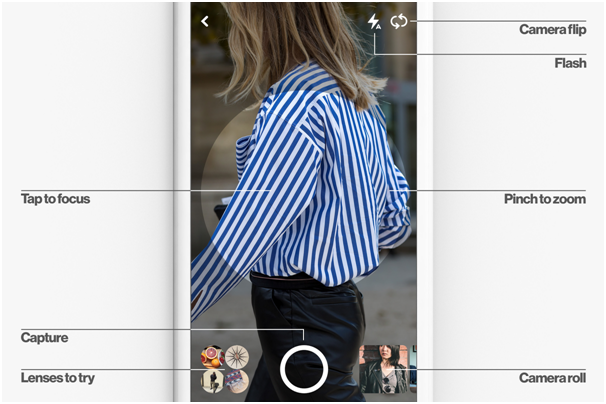

The launch of its Lens product in March this year was a real statement of intent and Pinterest has made a number of senior hires from Google’s image search teams to fuel development.

In combination with its establishment of a paid search product and features like ‘Shop the Look’, there is a growing consensus that Pinterest could become a real marketing contender. Along with Amazon, it should benefit from advertisers’ thirst for more options beyond Google and Facebook.

Pinterest president Tim Kendall noted recently at TechCrunch Disrupt: “We’re starting to be able to segue into differentiation and build things that other people can’t. Or they could build it, but because of the nature of the products, this would make less sense.”

This drives at the heart of the matter. Pinterest users come to the site for something different, which allows Pinterest to build different products for them. While Google fights war on numerous fronts, Pinterest can focus on improving its visual search offering.

Admittedly, it remains a work in progress, but Pinterest Lens is the most advanced visual search tool available at the moment. Using a smartphone, a Pinner (as the site’s users are known) can take a picture within the app and have it processed with a high degree of accuracy by Pinterest’s technology.

The results are quite effective for items of clothing and homeware, although there is still a long way to go before we use Pinterest as our personal stylist. As a tantalising glimpse of the future, however, Pinterest Lens is a welcome and impressive development.

The next step is to monetize this, which is exactly what Pinterest plans to do. Visual search will become part of its paid advertising package, a fact that will no doubt appeal to retailers keen to move beyond keyword targeting and social media prospecting.

We may still be years from declaring a winner in the battle for visual search supremacy, but it is clear to see that the victor will claim significant spoils.

source https://searchenginewatch.com/2017/07/05/everything-you-need-to-know-about-visual-search-so-far/

No comments:

Post a Comment